This text is an original copy from http://www.skeptictank.org/treasure/GP1/ANTARC3.TXT

TL: GREENPEACE 1992/93 ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION REPORT

SO: Greenpeace Interanational (GP)

DT: April 11, 1994

Keywords: environment greenpeace antarctica conferences

agreements terrec /

GREENPEACE INTERNATIONAL

Keizersgracht 176

1016 DW Amsterdam

The Netherlands

Phone: 31 (0)20 523 6555 Fax: 31 (0)20 523 6500

Printed on 100% chlorine-free paper

Contents

Section A Introduction

Section B Overview of Findings

1 ARGENTINA: Almirante Brown

Section C

SV Pelagic Voyage to the Antarctic Peninsula

2 ARGENTINA: Decepcion

3 ARGENTINA: Jubany

4 ARGENTINA: Refugio Naval Gousse, Peterman Island

5 ARGENTINA: Yankee Harbour

6 BRAZIL: Bardo De Teffe'

7 BRAZIL: Comandante Ferraz

8 BULGARIA: Refuge

9 CHILE: Teniente Marsh/Presidente Frei

10 CHILE: Capitan Arturo Prat

11 CHILE: Risopatron

12 CHILE: Gonzalez Videla (Abandoned Base)

13 CHINA: Great Wall

14 CZECH REPUBLIC: Vaclav Vojtek

15 ECUADOR: Maldonado

16 ECUADOR: Refuge, Admiralty Bay

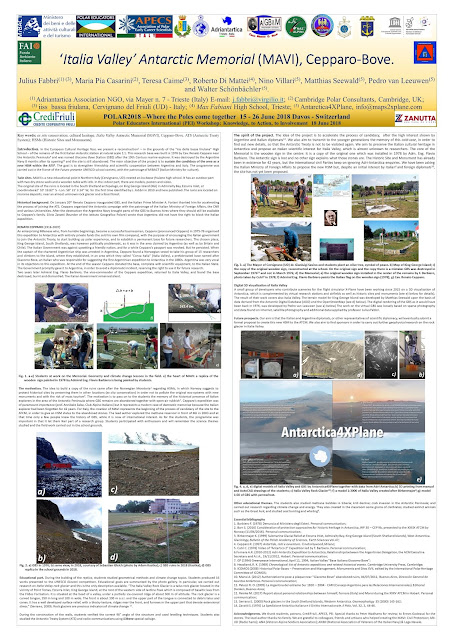

17 ITALY: Italian Valley "Base Italiana Giacomo Bove"

18 REPUBLIC OF KOREA: King Sejong

19 PERU: Machu Picchu

20 POLAND: Arctowski

21 RUSSIA: Bellingshausen

22 SPAIN: Gabriel De Castilla

23 SPAIN: Juan Carlos I

24 CUVERVILLE ISLAND

25 UNITED KINGDOM: Danco Hut

26 UNITED KINGDOM: Faraday

27 UNITED KINGDOM: Port Lockroy (Abandoned Base)

28 UNITED KINGDOM: Whalers Bay (Abandoned Base)

29 URUGUAY: Artigas

Section D MV Greenpeace Voyage to the Ross Sea

1 GERMANY: Gondwana

2 ITALY: Icaro Field Camp

3 ITALY: Terra Nova Station

4 NEW ZEALAND: Scott Base

5 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: McMurdo

6 Kapifan Khlebnikov

Section E Greenpeace: World Park Base Site

ANNEX I: Expedition Science Projects

REFERENCES

A INTRODUCTION

The 1992/93 summer marked Greenpeace's eighth year of operation

in the Antarctic. The organisation undertook two expeditions, one

to the Ross Sea region and the other to the Peninsula. The

results are presented in this report.

For over ten years, the focus of the Greenpeace's Antarctic

campaign has been to have the southern-most continent and the

surrounding ocean declared a World Park. This would be a zone of

peace, dedicated to international scientific research, in which

wilderness values are paramount.

With the signing of the Madrid Protocol on Environmental

Protection in October 1991, the international community moved one

step closer to this goal. Since then, Greenpeace has been working

towards the ratification of the Protocol by all

Antarctic Treaty parties.

From 1987 to 1992, Greenpeace maintained a year-round base at

Cape Evans to monitor the impact of human activity on the

environment and to provide a continuous presence against

possible minerals exploitation. The base was constructed during

the 1986/87 summer season, and decommissioned and completely

removed during the 1991/92 summer season. The Cape Evans site

also underwent a thorough clean-up and is the subject of an on-

going human impact study.

1 Ross Sea Expedition Description

The Ross Sea leg of the expedition used the Greenpeace vessel MV

Greenpeace. Much of this trip was devoted to following the

Japanese whaling fleet to protest their activities and to

promoting the proposed Antarctic Whale Sanctuary. However, the

itinerary included several Antarctic bases in the Ross Sea, and

well as the site of the former World Park Base, at Cape Evans,

Ross Island.

1.1 Expedition Itinerary

The MV Greenpeace departed Fremantle, Australia, on 21 November,

1992, and arrived Hobart, Australia, on 29 November. The ship

left Tasmanian waters on December 8 and reached the ice edge at

64°46'S 153°06'E six days later.

During the next six weeks, the MV Greenpeace patrolled the

whaling grounds. On February 2, the ship headed for the Ross Sea,

but was delayed by storm conditions, during which a

helicopter was damaged. This resulted in a brief stop for

maintenance at Relay Bay, Cape Adare. No one went ashore.

On February 10, the MV Greenpeace reached Cape Evans, where the

crew established a temporary field camp. Three to five crew

members conducted further environmental monitoring at the former

site of World Park Base. During this time, the MV Greenpeace made

a brief trip across McMurdo Sound to Marble Point.

The MV Greenpeace left Cape Evans for McMurdo during the evening

of February 15. The expedition spent the following two days at

Scott Base and McMurdo Station and departed for the Bay of

Whales on February 17, in the late afternoon.

The Japanese whaling fleet's factory ship, Nishan Maru, was

intercepted on February 18, but the encounter, played out in

stormy weather, lasted only a few hours. On February 21, the MV

Greenpeace reached the Bay of Whales, and on February 25, the

ship had brief contact with one of the Japanese catcher boats,

the Toshi Maru No. 25.

The expedition's final stop in the Antarctic was Terra Nova Bay,

where the MV Greenpeace arrived on February 28. After brief

visits at the German and Italian stations, the ship left for

Auckland on March 1.

However, two days later, Greenpeace was asked to stop at

Campbell Island to evacuate a staff member who needed medical

attention. The ship arrived and departed Campbell Island on March

8 and reached Dunedin, New Zealand, on March 10. The

expedition concluded four days later in Auckland.

1.2 The MV Greenpeace and Crew

The MV Greenpeace is a 58-metre converted ocean-going tug,

registered in the Netherlands. The ship's hull was ice-

strengthened in 1985. She made trips to the Ross Sea region in

1986,1987, and 1988, to the Antarctic Peninsula in 1987/88, and

spent time in Antarctic waters during the 1991/92 season.

On this trip, the MV Greenpeace carried 30 crew from 12 nations.

Almost 90% of the crew had sailed with Greenpeace before and over

half had worked previously in the Antarctic.

The MV Greenpeace was skippered by Danish master Arne Sorensen,

with first mate David Iggulden. The expedition leaders were Naoko

Funahashi and Kieran Mulvaney, and Dana Harmon directed the shore

work. Scientific research was conducted by Grant

Harper.

Photographer Martin Leuders and cameraman Alex de Waal

documented the trip for Greenpeace, and their material is

available from Greenpeace Communications in London, UK.

2 Peninsula Expedition Description

In a change from previous expeditions, and with no base to

resupply, Greenpeace decided to trial a smaller and simpler

method of transport, chartering the yacht SV Pelagic rather than

using one of Greenpeace's own ships. This was seen as a more

environmentally friendly form of transport, as the amount of

fossil fuel burnt over the course of the voyage was a fraction of

that burnt by a ship, and the impact of eight people was less

than that of a crew of thirty.

The itinerary of a short ocean voyage followed by several weeks

around the Antarctic Peninsula, where shelter is always

available for a small yacht, made the plan feasible.

2.1 Itinerary

The SV Pelagic departed Ushuaia, Argentina, on 31 December, 1992,

and arrived at Maxwell Bay, King George Island, on January 4,

1993. After spending nine days in Maxwell Bay, the Pelagic sailed

to Admiralty Bay, King George Island, where it remained for a

further five days. The yacht then headed, via Greenwich Island

and Livingston Island, to Deception Island, where it stayed for

four days due to bad weather.

After leaving Deception Island on 26 January, the yacht headed

south to the Antarctic Peninsula, calling in at Cuverville

Island, Paradise Harbour, and Peterman Island, before reaching

Faraday station (UK) on 30 January. From Faraday, the Pelagic

sailed north, visiting Port Lockroy and Yankee Harbour before

attempting to enter the Drake Passage. This attempt was

frustrated due to bad weather, and the Pelagic sheltered for two

days in the harbour behind Arturo Prat station (Chile) on

Greenwich Island. It finally entered the Drake Passage on 6

February, arriving in Ushuaia on 12 February.

2.2 Yacht Specifications and Crew

The SV Pelagic is a 25 tonne steel-hulled sloop, 16.5 metres

long, with a retractable keel and rudder.

Eight people sailed on board the Pelagic: the skipper, first mate

and six Greenpeace personnel. Six nationalities were

represented amongst the team, and all except one had previous

Antarctic experience.

The yacht was skippered by its owner, Skip Novak, with first mate

Julia Crossley. The expedition leader was Janet Dalziell; Ricardo

Roura carried out the science program; and camera

operator Bruce Adams and photographer Jorge Gutman documented the

trip.

3 Greenpeace Expedition Procedures

Prior to arriving in the Southern Ocean, everyone on board the MV

Greenpeace and the SV Pelagic received information and

training on the unique nature of the Antarctic environment and

the procedures to be followed to protect it.

Once the vessels entered Antarctic waters, all solid waste was

stored on board. North of the Antarctic convergence, only food

scraps were dumped overboard. All other waste was returned to New

Zealand and Argentina for disposal, and, where possible,

recycling. Sewage from the MV Greenpeace went through a

biological treatment process before it was released. Sewage from

the SV Pelagic was released directly into the sea.

More specific instructions were given to both crews before each

landing, and experienced field personnel accompanied all shore

parties. Safety information for shore activities and ship travel

was also covered extensively. In addition, crew members were

familiar with Treaty regulations and had access to official

literature.

Base inspections were carried out under the supervision of

expedition campaign staff. Inhabited stations were always

advised of Greenpeace's intent to visit the base area at least 24

hours prior to arrival. Crew members did not enter any

buildings without an invitation from station management or

personnel. Whenever time and weather permitted, base staff were

invited to board and tour the MV Greenpeace and the SV Pelagic.

B OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS

While this report concentrates on describing the stations

inspected during the 1992/93 austral summer, Greenpeace would

also like to highlight some broader observations made over the

course of the expedition.

1 Abandoned Sites

One of the striking things about the 1992/93 Peninsula

expedition was the number of clean-up tasks that a yacht crew of

eight was able to accomplish, in short periods of time and

without requiring specialised equipment. At one site, the crew

emptied rusting barrels of fuel that had started to leak into the

environment; at another site, they secured loose waste and

barrels of fuel; and at a third site, they picked up tangles of

copper wires that had trapped penguins and stored it inside a

building.

These tasks were small and simple, and it was difficult to

understand why they had not been done by one of the many ships

that ply the Peninsula waters every summer. One common reason

given for inaction is that government X does not have

jurisdiction over the abandoned property in question. This

excuse is particularly disturbing in cases of joint use such as

the hut at Peterman Island. This was originally an Argentine

facility, which is now used for recreation by personnel from the

UK's Faraday station and is frequently visited by tourist ships.

With respect to this problem, the Protocol's Annex III is quite

clear (Art 1(5)):

Past and present waste disposal sites on land and abandoned work

sites of Antarctic activities shall be cleaned up by the

GENERATOR of such wastes and the USER of such sites (emphasis

added).

2 Knowledge of the Protocol

Another disturbing trend noticed by Greenpeace was that, over a

year after the Protocol's completion and signature, station

personnel lacked information about the agreement and its

ramifications for Antarctic operations. In the worst case,

Greenpeace found that station personnel at the Uruguayan station

of Artigas did not even know of the Protocol's existence.

3 Protected Areas

Greenpeace once again checked and repaired the signs at

Deception Island that mark the Whalers Bay and Pendulum Cove

parts of the Deception Island Site of Special Scientific

Interest (SSSI). However, it is increasingly clear that the

Deception Island SSSI has become something of a farce;

Greenpeace has directly documented violations of two of the five

parts to the site (Whalers Bay and Telefon Bay), and has strong

anecdotal evidence that at least one other part (Pendulum Cove)

has been entered frequently by tourists.

4 Environmental Impact Assessment

Environmental impact assessment (EIA) requirements and

procedures appear to be among the aspects of the Protocol that

are least understood and followed. At several stations,

Greenpeace found that construction work was done in recent years

without any evidence of prior environmental impact assessment. At

most stations, leaders had little knowledge of the topic. This is

an area where exchanges between countries could be very

beneficial, so that nations with well-established domestic EIA

requirements could share their skills with other Treaty members.

C SV Pelagic Voyage to the Antarctic Peninsula

1 ARGENTINA: ALMIRANTE BROWN

1.1 Overview

Almirante Brown was built in 1951. It remained abandoned for a

number of years after a fire in 1984. Basic repairs and a clean

up were done during the 1988/89 season, and it is now used as a

summer science camp.

The station is run jointly by the country's Direccion Nacional

del Antartico (DNA), which owns and maintains the facility, and

the Instituto Antartico Argentino (IAA), which directs the

research program The Argentine Navy, the Armada Argentina (ARA),

provides logistical support for the resupply.

1.1.1 Location

Almirante Brown is located in Paradise Bay on the Antarctic

Peninsula. The station is sited on a small, rocky apron which

protrudes into Paradise Bay. Brown is confined to the ice free

area, bordered by a snow and moss-covered slope which rises

steeply behind its buildings.

1.1.2 Status

At the time of Greenpeace's visit, the OIC was Lic. Jorge Gallo,

who is the head of the Marine Sciences department of IAA. He was

to be at Brown from December 1992 until March 1993.

There were 11 staff on station for the summer, comprising ten

scientists and one logistics person. The scientists were a mix of

IAA employees, researchers from Mar del Plata and La Plata

Universities, and a navy hydrographer. The logistics officer was

an employee of DNA. The station was therefore run by DNA,

although transportation is provided courtesy of the navy.

Date and Description of Contact

Greenpeace visited Almirante Brown on 28 January, 1993. The visit

consisted of a fairly brief and informal discussion with base

personnel.

1.1.4 Previous Visits

Greenpeace's first visit to Brown took place in April, 1988,

during the 1987/88 expedition to the Antarctic Peninsula.

Greenpeace made three more visits to Almirante Brown in

November, 1989 and March and April, 1991, details of which may be

found in the expedition reports from those seasons.

1.2 Physical Structure

The station consists of seven structures of various sizes: an old

main house and lab facility, generator room, three sheds, an

emergency hut and an emergency generator room.

Most of these structures are derelict, having been destroyed by a

major fire in 1984. The emergency hut was in reasonably good

condition, although the paint was beginning to flake off.

The current summer camps occupy the emergency hut and use the old

laboratory and generator room. There are no roads within or

leading out of the station. The station's two jetties were in

poor condition. All transport is by boat; personnel were brought

in and retrieved by ship, and two inflatable boats are used to

travel around the immediate area.

The base is visited relatively frequently throughout the year, by

tourist ships and Chilean naval ships that patrol the area.

Water is obtained from the meltstream below the glacier, and,

when necessary, by melting ice.

1.3 Operations

Science under way at the station was mostly oceanographic work of

various types. One of the major projects studying samples of

seawater for contamination by hydrocarbons, heavy metals, and

pesticides. In the future, studies on contamination of limpets

and bivalves are to be added to this.

The OIC said that "sooner or later" the old ruins of the base

will be cleaned up. Apparently some clean-up had been under way,

but was interrupted when the Bahia Paraiso sank in early 1989.

Certainly, much more work would be needed before any rebuilding

of the station could be contemplated.

1.3.1 Waste Disposal Systems

1.3.1.1 Separation

Waste is separated at source in the galley and laboratory into

burnables (wood, paper, cardboard and organics), plastics, glass

and tins. Over the summer, about two 200-litre drums of tins, one

of plastic, and two of glass were likely to be produced. Waste

for removal was either stored in plastic bags or in the wooden

boxes in which food supplies were brought.

Little attempt is made to reduce packaging prior to supplies

being brought to Antarctica. Food is sent to the base in its

usual packaging, inside plastic bags in wooden boxes. This

system is partially justified because food is stored outside and

the plastic bags therefore give the provisions some protection.

Laboratory chemicals in use included formalin and lugol. These

were disposed of into buckets which were then tipped into drums

for removal.

The OIC reported that a general clean-up of the station would be

done at the end of the summer.

1.3.1.2 Dumps

While there did not appear to be a dump per se, a lot of old

material was stacked around the site. Under the generator room

were the carcasses of at least 10 vehicle batteries. Several of

these had been knocked over, most were in poor condition, and one

was broken. Apparently four or five penguins had attempted to

nest amongst this rubbish. Eight barrels filled with waste oil

products could also be seen.

By the emergency hut (where the camp team now live), there were

22 200-litre drums full and half-full of waste oil and fuel,

alongside which were two plastic bags filled with garbage,

buried in the snow.

The base area was haphazardly littered with coal, sand, cement,

battery acid and fuel which had leaked from corroded drums.

1.3.1.3 Incineration

"Burnable" waste is burnt in a simple brazier located outside the

living quarters. The brazier comprises a 200-litre drum with a

grid near the bottom and holes to improve air circulation.

Emissions are neither filtered nor monitored.

As the brazier had a lid, organics were not accessible to

wildlife.

Burnable waste included some types of plastic, including plastic

rubbish bags holding organic waste.

The logistics person was in charge of burning waste.

In addition to the garbage burning, the station also has

barbecues over open fires, which are lit directly on the ground.

1.3.1.4 Waste Removal

Removal of garbage takes place at the end of the summer season on

the icebreaker Almirante Irizar. In addition to the main

logistics visit, the station sometimes receives visits from other

navy vessels and tourist ships, which occasionally remove some of

the station's garbage.

Besides 'non burnable' wastes, ash from the burn-drum reportedly

is also removed.

Garbage is returned to Argentina, although the actual port to

which it is shipped depends on the itinerary of the resupply

vessel. It is unclear whether any of the waste is reused or

recycled.

Base personnel reported that while the summer's waste tends to be

removed, a much lower priority is placed on the removal of old

waste. Several containers (bags and drums) of garbage, and stacks

of old building materials that had been there at the time of

Greenpeace's previous visit in April 1991 were still at the base

on this occasion.

1.3.2 Sewage System

Sewage and grey water are poured raw into the sea through a

sewage outfall that ended on the rocks by the shore, about a

meter above the high water mark. Human faeces could be seen on

the rock surface below the pipe.

1.3.3 Energy Systems

The base was using up to two drums of diesel each month. In

addition to the diesel currently in use, which was stored in

drums, there were about 20,000 litres of diesel left in the old

fuel tanks. The OIC said that this was slowly being removed by

yachties.

Fuel was transferred from ship to shore in drums, using

helicopters or inflatable boats. Within the base, fuel was

transferred using hand pumps. The generators were connected

directly to the drums in use.

A cluster of around 22 drums, in various conditions, sat in front

of the living quarters. Of these, at least one had rusted through

and released its contents into the ground. There were four newer

drums sitting on the glacier, several tens of metres from the

living quarters. Next to the old generator shed, there were a

further 35 drums in poor condition. Some of these had small

quantities of oily water inside. And finally, stacked along the

main jetty were around 30 drums containing waste fuel and oil. At

least two of these were leaking.

As reported from Greenpeace's last visit, one of the large old

fuel tanks was leaking. The drip tray that had been sitting

underneath the leak (and overflowing) at the time of

Greenpeace's previous visit could be seen lying in the sea

nearby. There was also at least one leaking fuel drum, and base

personnel said that they were waiting for another drum to be

emptied so that they could decant fuel out of the leaking one. A

pipeline that runs under the generator room was leaking fuel, and

substantial staining of the soil underneath the generator shed

was observed.

The base has one portable and two permanent generators, one by

the emergency hut/living quarters (15 kW), and one by the

laboratory (25 kW). The first was used for approximately four

hours each night, and the second was used on demand, on average

for about three hours a day. All work that required electricity

was done during those periods. Because little fuel was used,

transfer of fuel was rarely required. None of the generators had

drip trays or filters.

There was no alternative energy production at the base.

1.4 Tourism

During summer, the base is visited at least once a week by

tourist ships, as well as by the occasional yacht. By the date

Greenpeace called in, visits had been received from the

Molchanov, Vavilov, Explorer, World Discovery, Illiria, Northern

Ranger, and Vistamar. Base personnel reported that tourist

visits seem to be increasing.

1.5 Evaluation of Environmental Impact

When asked what he thought was the most serious environmental

impact of the station, the OIC said that he thought the worst

impact had probably come from the fire that destroyed the base.

Before coming to Antarctica, people staying at the base had

received two to three lectures at IAA which covered safety, other

aspects of Antarctic operations as well as environmental

protection. Each station or camp leader (OIC) had been given a

copy of the Protocol in a meeting with the director of IAA. There

was therefore a copy of the Protocol on the base. There is

abundant wildlife around the station (antarctic terns, Wilsons

storm petrels, sheathbills, blue-eyed shags, gentoos, crabeater

seals, humpback and minke whales). The terns and shags breed on

the cliffs near the station. There are also several species of

moss on the slopes of the hill behind the base. A path to the top

of the hill at times traverses these patches of moss.

Skuas were seen begging at the door of the kitchen, suggesting

that they are sometimes fed. Greenpeace was told that one or two

of the base personnel had been feeding skuas to try to tame them.

Apparently, penguins have tried to nest under the

generator shed, where acid and fuel has leaked.

The base personnel did not feel that they had jurisdiction over

the wildlife in the area, and therefore had no formal guidelines

to give visitors. However, base personnel expressed concern that

sometimes visiting tourist ships do not even bother to contact

the base or reply to their calls.

1.5.1 Comments and Recommendations

It was obvious that little has been done to improve the site

since Greenpeace's last visit. In particular, the same fuel leaks

were still dripping, and the same piles of rubbish and building

materials were still lying around. There is also a lot of more

recent litter lying around the station.

Therefore, many of the recommendations here are similar to those

presented after Greenpeace's previous visit two years ago.

The fuel storage situation demands immediate improvement. Fuel in

the old fuel drums and tanks should be decanted into sound

containers and the old tanks and drums should be removed to

prevent further leakage of fuel into the environment. Fuel

facilities that are kept for the use of summer camps should be

provided with containment facilities, as should the generators.

All other old materials and rubbish lying around the site,

particularly hazardous and toxic materials such as batteries,

should be removed. The whole site clearly needs a major clean-up

effort.

Further field camps should not burn their wastes; all wastes

should be removed from the Antarctic.

Should Argentina plan to operate this camp in the long term, the

possibility of cooperating with the Chileans in Paradise Harbour

should be investigated.

Feeding of skuas should be strongly discouraged.

2 ARGENTINA: DECEPCION

2.1 Overview

Decepcion was established by Argentina in 1947 but has only been

used sporadically since 1967, when it was evacuated during a

volcanic eruption. It has been used as a field camp since 1988.

Officially, the camp is run by the Armada Argentina (Navy).

2.1.1 Location

Decepcion is located at Fumarole Bay, Deception Island, and sits

on a flat area at the foot of a hill, surrounded on two sides by

a lagoon and on a third side by Port Foster.

2.1.2 Status

At the time of Greenpeace's visit, the OIC was Dra. Corina

Risso, of the Earth Sciences Department, Buenos Aires

University. The team were scheduled to be there from late

November to late February. There were eight people in total (all

scientists), four of whom were Spanish researchers, led by Dr.

Ramon Ortiz, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones de Espana.

The station itself is in a state of disrepair and is not used as

a fully functioning station, but as a field camp.

2.1.3 Date and Description of Contact

Greenpeace visited Decepcion on 23 January, staying for

approximately three hours.

2.1.4 Previous Visits

Previous visits to Decepcion took place during the 1987/88,

1989/90, and 1990/91 Greenpeace Antarctic expeditions.

2.2 Physical Structure

Decepcion consists of a main building which has several separate

additions, five small buildings of different sizes and

functions, and a large emergency building.

Volcanic activities have caused ash slides which have partially

buried several buildings, tanks, and many fuel barrels. The old

main station building is derelict and half filled with ice.

There are no formed tracks in the area. The station has a

rundown helipad and jetty.

2.3 Operations

Water for the camp is taken from a well protected by a small

shed.

Travel around the island is mostly done on foot, although the

base also had an inflatable boat.

Scientific programs underway at the camp were geological and

geophysical research on volcanology. Most of the program

involved placement and monitoring of sensors at various sites

around Deception Island, and monitoring volcanic gases.

2.3.1 Waste Disposal Systems

Household waste was separated into burnables (organics, paper,

cardboard and wood) and non burnables, which were burned and

removed from Antarctica respectively.

A field chemical lab had been installed in one of the rooms of

the building used by the camp. There were no sinks in this lab.

Removal of waste was to be done by ship when the camp was taken

out. Waste was to be returned to Argentina. Bags and boxes of

glass and cans were stacked behind the boat shed on the beach

awaiting removal.

"Burnable" waste was burnt in an open drum. Emissions were

neither filtered nor monitored.

There were several old dumps in the vicinity--both near the old

main building, and along the shore to the southeast--that

appeared to be no longer used, and may have been partially

buried by volcanic ash. These contained glass, metal junk, fuel

drums, construction materials, electrical fitting, and a

solidified tarry substance.

Inside the old main hut were collections of laboratory and

medical chemicals. There were also glass vials in each room which

are conjectured to contain carbon tetrachloride for

firefighting.

2.3.2 Sewage System

Sewage and grey water were put into the three-stage septic

chamber belonging to the station.

2.3.3 Energy Systems

The camp was using around 400 litres of diesel fuel each summer

in two portable generators that were only run for a few hours

each day. Eight to ten drums of diesel were stored outside the

emergency hut in which the team was camping. These had been

transported ashore from the ship by helicopter. There was also

some petrol on site for the outboard engine.

The Spanish team had two small wind generators installed to run

the scientific equipment, as the portable generators provided

insufficient and unreliable power.

There were several drums and tanks left at the site which

belonged to the old station. Some were partially buried, and

there may be others that have been completely buried. These will

pose a threat to the local environment as they deteriorate and

leak, although it appears possible that most are already empty.

2.3.4 Resupply Operations

The camp is visited by a resupply ship twice a season, at the

beginning and the end of the summer.

2.4 Tourism

No tourists visit this station, although reportedly one company

earlier in the season had investigated the possibility of taking

groups of tourists over the island to the nearby penguin

rookery.

2.5 Evaluation of Environmental Impact

When asked what she considered to be the greatest environmental

impact of the station, the OIC said that the impacts of the camp

itself were very minor.

While this may be true, the old, essentially abandoned station

contains toxic and hazardous chemicals, and there is possibly

still a considerable amount of fuel at the site.

Decepcion is located in the part of Deception Island that the

vulcanologists think is most likely to erupt soon. This may be

contributing to a lack of clean-up action on the part of the

Argentine navy, who may be hoping that the problem will solve

itself by being blasted away in an eruption.

A document describing the concepts of the Protocol was available

at the camp, and computer printouts of cartoons about

environmental protection and Antarctic safety were pinned around

the walls of the living area.

The station is located near the Fumarole Bay section of the

Deception Island SSSI. The scientists visit the SSSI regularly to

monitor the fumaroles and collect gas samples.

2.5.1 Compliance with the Protocol

As mentioned above, information about the Protocol was available

on station.

2.5.2 Comments and Recommendations

The possibility that the Decepcion site might be destroyed by

volcanism in the near future does not, in Greenpeace's opinion,

excuse Argentina from its obligation to clean up the site. In

fact, the likelihood that old garbage, fuel contamination, and

laboratory chemicals might be scattered through the area should

provide extra impetus to move toxic materials from the danger

zone.

A particularly easy job would be to remove the remaining

medical, science, and firefighting chemicals from the old

buildings. This should be done forthwith.

Burning should cease at Argentine field camps. Given their

inherently portable nature, it should not prove difficult to

devise systems for storing ALL garbage for removal at the end of

the summer season.

3 ARGENTINA: JUBANY

3.1 Overview

Jubany Station was constructed in 1953, and has been operated

since 1984 as a year-round station. It is the only civilian base

in the Argentine Antarctic program.

3.1.1 Location

Jubany Station is located in Potter Cove, King George Island,

South Shetland Islands (62°14'S,58°40'W). The station is built on

two levels, between five and 15 metres above sea level. As the

buildings are spread out along the shore, the total area covered

by the station is reasonably large. It was suggested by station

personnel that one of the reasons for this spread was to prevent

other countries from setting up a station nearby.

A stream, contained by a concrete dam and cement bags, runs

through the station area.

Approximately 500 metres from the main station complex is the

boundary of SSSI no. 13 (Potter Peninsula).

3.1.2 Status

The OIC at the time of Greenpeace's visit was Mayor (Major)

Victor Foster, from the army, Jubany's first military OIC. He was

to be in charge until July 1993. The Second-in-Command and base

manager was Suboficial-Mayor Miguel Paz.

Normally, there would be 30-40 people on station during the

summer, but in 1993 numbers had been swelled to 64 by

construction personnel. There were approximately 25 scientific

staff on station at the time of Greenpeace's visit, including

four German biologists.

In winter the team consists of 12 to 20 people.

The scientists are mostly employed by the Direccion Nacional del

Antartico (DNA). Base logistics are run by the army (Ejercito

Argentino, (EA)). The construction workers included a mix of

personnel from different army forces including EA, gendarmeria

(border police), prefectura (coast guards) and Argentine navy.

Jubany is the only Argentine station which has scientific

research as its primary function. It used to be entirely run by

DNA but during 1993 logistics were carried out by the EA. It was

not clear whether the army was has been called in to run the

logistics of the station permanently, or whether the army's

presence would be merely temporary for the duration of the

construction.

3.1.3 Date and Description of Contact

Greenpeace visited Jubany on 6 January 1993. The visit included a

meeting with the OIC, lunch, and an extensive tour of the

station.

3.1.4 Previous Visits

Greenpeace previously visited Jubany Station on two occasions. A

description of the first visit, carried out in early

April,1988, can be found in the report from the 1987/88

Greenpeace Antarctic Expedition. The findings of the second

inspection, undertaken in late October 1989, are contained in the

1989/90 Expedition Report.

3.2 Physical Structure

The main part of the station consists of three large buildings

that house the living quarters, as well as 12 smaller buildings

containing laboratories, generators, etc. In addition, there were

four fibreglass "apple" huts, tents, and a shipping

container that were used by one of the visiting German

scientists.

Most of the buildings are clad in wood, although one of the

larger buildings appears to have a metal frame with fibreglass

cladding. In general the structures seemed to be in reasonably

good condition.

The dam in the stream was once used as the water supply for the

station and for ships. The dam structure looked old and in poor

condition. The station's water supply now comes from two lakes

behind the station, which apparently provide ample water for

summer. In winter, trucks are used to collect ice from the

lakes, once a week.

Transportation facilities include an airstrip on the glacier, a

helipad, and two large mooring bollards on the beach.

The station maintains two field huts in the nearby SSSI. These

are reached along well-defined tracks through the SSSI, usually

on four-wheeled motor bikes.

In addition to the two tracks into the SSSI, there is at least

one track leading up onto the glacier, to the airstrip. Tracks

also lead to the SW navigation light, to the separation garbage

location/dump, to the heliport northeast of the main cluster of

buildings, and to a pond which is sometimes used as an

alternative water source.

As well as the formed roads, vehicle track marks could be seen

over most areas.

3.2.1 New or Upgraded Facilities

Two large buildings were under construction at the time of

Greenpeace's visit. One is intended to be a laboratory, and the

other will house generators. A substantial amount of

construction material was lying around in the vicinity of the

construction site. The new buildings are constructed of

insulated fibreglass panels on steel frames, with concrete

foundations. A document discussing this construction was

circulated at the XVIIth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting in

Venice, in November 1992.

The new laboratory is a joint project between Argentina and

Germany, initiated because the existing laboratory facilities at

Jubany were too small for the Argentine scientists, let alone for

an additional German contingency. Germany was reportedly

consolidating all its Antarctic operations on King George Island

to Jubany.

At the time of the visit, the vehicle workshop was also being

enlarged. Elsewhere, excavations appeared to have been done for

more foundations, although this disturbance looked old.

3.3 Operations

The scientific program at Jubany includes studies on coastal

oceanography, ecosystem monitoring projects for CCAMLR, coastal

ecology (including a major baseline study of the area),

ichthyology, and satellite imagery. Some of these projects a re

run jointly with the German scientists on station, and Dutch

scientists were also collaborating on a couple of projects.

In addition, an ongoing program of psychological research is

under way.

The programs studying birds and mammals involved some handling of

animals--mainly weight measurements and stomach content

analysis. In the case of elephant seals, this included the use of

anaesthetics. Blubber cores were also being taken from live

elephant seals for pollution analysis. Small quantities of fish

were being taken for the ichthyology work.

Vehicles on station included at least two small trucks, some

four-wheeled motorbikes, and at least one tracked tractor. In

addition, a skidoo lay dismantled near the workshop. For water

transport, the station had four or five inflatable boats.

Scientists are transported in and out by Twin Otter aircraft, via

the airstrip at Marambio and sometimes via Marsh. Station

personnel are exchanged by the Irizar, which visits at least once

each season.

Waste Disposal Systems

3.3.1

3.3.1.1 Separation

Station personnel told Greenpeace that waste is separated into

metal, glass, plastics, and burnables. However, the only

material Greenpeace saw stacked for removal were drums of

crushed tin cans. Everything else appeared to be burnt.

The station's Second in Command (SIC), who is in charge of waste

disposal, said that food scraps are burnt. One of the biologists

added that this practice had only started that year, and that it

was adhered to reluctantly. Food scraps were seen lying on the

ground in the "separation" area a short distance from the main

part of the station. Numerous begging skuas were seen loitering

around the station, particularly behind the kitchen.

There are two areas where rubbish is handled. By the helipad was

a large collection of drums containing metal rubbish, which

appeared to have been there for several years. Further inland is

a natural depression in which rubbish appears to be sorted.

Station personnel said that this area is difficult to work in

when it is windy, as rubbish tends to scatter.

3.3.1.2 Dumps

There were no clearly defined dumps, but in some places the soil

contained significant quantities of glass and metal scraps, and

it seemed conceivable that these areas (in particular the bank

between the station and the shore) may be old dumps that have

been bulldozed over.

A pile of loose, rusty scrap wire, surrounded by broken glass,

lay in the sand below the sorting area. Around the station were

numerous heaps of solidified cement which appeared to be

stockpiles of cement bags that had gotten wet.

3.3.1.3 Incineration

Much of the waste appears to be burnt in the drums scattered

around the station, and particularly in the sorting area

described above. Station personnel said that only wood and

cardboard are burnt. However, other partially burnt objects seen

in the ashes included cans, lightbulbs, and aerosol cans.

3.3.1.4 Waste Removal

Stacked for return to Argentina were 170 barrels of crushed metal

waste. It was marked (in Spanish) "Packed rubbish to be returned

to the continent (03.02.89)." Also waiting removal were 52

cooking gas (Agipgas) canisters.

Several ships call at Jubany each summer, including the

Argentine's main resupply vessel, the navy icebreaker Almirante

Irizar. However, it appears that they seldom take on board

rubbish for return to Argentina. The SIC said that no rubbish had

been taken out since his arrival at the station in September

1992. However, he was confident that it would occur sooner or

later when the ship had enough space, and he said that most of

the rubbish awaiting removal had been generated since his

arrival (i.e. there is hardly any old rubbish on site). This

seems to be partly contradicted by the pile of material dated

1989 by the helipad.

Both the OIC and SIC seemed dissatisfied with the current waste

disposal system. The OIC said that he was keen to install a

garbage compactor (he said that one had been purchased, but was

waiting on adequate cargo space).

The OIC reported that station-wide clean-ups are done once a

week, with two parties alternating throughout the season.

3.3.2 Sewage System

Sewage, including grey water, is poured, untreated, directly into

the sea. Greenpeace was told that the Germans plan to build a

treatment plant once the science laboratory building is

finished. The OIC reported that the sewage system was stretched

to its limits coping with 60 people on station, and he hoped to

introduce a system whereby solid waste from toilets can be

collected and burnt.

The sewage pipe ends above the beach, and a trickle of sewage was

visible on the beach from below the pipe to the water.

3.3.3 Energy Systems

Approximately 100,000 to 120,000 litres of diesel are stored at

the station, in six 20,000 litre bladders. The bladders sit on a

plywood platform, which rests on concrete piles, about 1.5 metres

off the ground. A day tank stands by the engine room. There are

no containment structures around any of the tanks.

The station was equipped with rolls of rubber-covered flexi-

hoses, and this may be the method that is used to move fuel from

ship to shore. From the bladders to the generators, fuel is

pumped through a small-bore steel pipe lying along the ground.

Another fuel transfer method used by Argentina is by flying 2000

litre metal tanks by helicopter from the icebreaker.

In places, the bladders were seeping fuel. One bladder had a pool

of diesel sitting in the depression around the valve on the top

of the bladder. While there were no visible stains in the soil

below, the sandiness of the soil probably means that fuel is

absorbed very quickly. In addition, it appeared that the wood of

the platform on which the bladders sit soak up some of the

spilled fuel.

Station personnel said that one of the bladder tanks had leaked

in late winter and all through the 1991/92 summer, and that

enough fuel was spilt for some to migrate through the soil to the

sea, about 80 metres downslope.

It is planned to replace the bladders with steel tanks that will

sit on the same concrete foundations currently supporting the

bladders.

There are no alternative energy systems at Jubany.

3.4 Tourism

Jubany receives a few visits from tourists each summer. Tourists

are shown around the station and up to the boundary of the SSSI

(which they are not permitted to enter) by the station

scientists. A complaint heard from some station personnel was

that the station gives a high priority to these visits because

they provide an opportunity to promote Argentine sovereignty in

the region. However, guidelines are reportedly being written that

will clearly establish science as the priority activity.

3.5 Evaluation of Environmental Impact

The OIC and the SIC (who have been working as a team for many

years) were mostly concerned about the rubbish and its visual

impact. They said that they have undertaken a major clean-up of

the station to get rid of items like waste drums, and that they

had already removed a lot of rubbish since the beginning of the

1992/93 summer.

The blockage in the system seems to be ship space for removal of

wastes. The OIC said that there is a lot of competition among

Argentine Antarctic stations for access to space on ships.

A study of the environmental impact of the Argentine stations is

being addressed by a team of three scientists led by Jose Maria

Acero from the IAA.

Prior to their stint in Antarctica, the military personnel who

are wintering over receive about one year's training in the

Antarctic section of the army. The program covers survival,

safety training, etc., and approximately two weeks are

reportedly spent in training on environmental matters, courtesy

of the DNA. In addition, the scientists on station give some

training as to local wildlife and sensitive areas, with lectures

as soon as new people arrive on station. It was not made clear to

Greenpeace how civilian personnel are trained.

It seemed that the training was not completely successful, as,

for example, construction loads had been placed on top of

previously relatively undisturbed moss beds. In addition,

personnel were observed walking on the local plant cover.

The OIC had a copy of the Madrid Protocol ready to hand, and also

gave Greenpeace an IAA publication on the location of SSSIs and

SPAs and other Treaty rules. However, the OIC and SIC did not

seem to have a high degree of awareness about the role of

environmental impact assessments.

The station had a population of approximately 100 skuas. This

large number suggests that the birds are regularly fed. Terns

nest on the beach in front of the temporary summer

accommodation, and giant petrels breed in the nearby SSSI.

Vegetation is abundant around the station, and remains of plant

cover could be seen even in the middle of the station, albeit in

small patches. Vegetation was common in all areas except very

close to the beach.

The boundary of the SSSI was rather poorly marked with a sign

(placed quite high on the hillside) saying simply "Restricted

Area" in Spanish and English. There were no signs on the beach,

which would be a likely point of access. However, there was a

prominently displayed map inside the station showing the

boundaries of the area.

Station personnel are permitted to enter the SSSI as long as they

stay on the formed paths. During the visit, Greenpeace personnel

were encouraged to enter the SSSI to visit the

elephant seal colonies, although the OIC said that such a visit

should be accompanied by a scientist. Greenpeace staff did not,

however, enter the site.

3.5.1 Compliance with the Protocol

The main area where the station does not comply with the

Protocol is in its lack of sewage treatment.

The burning of plastics is also possibly a violation of the

Protocol, depending on the type of plastics that are burnt.

3.5.2 Comments and Recommendations

One of the station's biggest problems appears to be the waste

handling system. An immediate improvement that could be made is

much more effective sorting of garbage at source, with adequate

and clearly labelled containers available in all areas of the

station. Removal of waste needs to receive much more support,

program-wide, with a much greater emphasis placed on providing

adequate ship space and logistic time for removing garbage.

Burning of waste should be ceased immediately.

Plans to remove the fuel bladders are to be commended, and

should be carried out as soon as possible. However, containment

needs to be provided for all fuel facilities. Of course, the

amount of fuel that it is necessary to store on station could and

should be significantly reduced by the development and

installation of alternative energy systems.

Finally, the sharing of facilities with the German Antarctic

program is wholeheartedly encouraged. However, the increase of

personnel at the station will increase the urgency with which

Jubany must address its logistics problems discussed here.

4 ARGENTINA: REFUGIO NAVAL GOUSSE, PETERMAN ISLAND

4.1 Overview and Location

The hut on Peterman Island, Lemaire Channel, (65°11'S 64°10'W)

was built in 1955 by Argentina. It is located on the water's

edge, on a low rocky outcrop.

4.1.1 Status

The hut is now used for recreation by personnel from the UK

station Faraday, and is frequently visited by tourist ships.

4.1.2 Date and Description of Contact

Greenpeace visited Peterman Island on 29 January 1993, for about

2 1/2 hours.

4.2 Physical Description

The hut is situated in the middle of a large gentoo penguin

colony, which is the main reason for tourist interest in the

site.

The refuge consists of a hut, and a small tin shed that is

missing its roof and two walls. The hut looked rough from the

outside, but was clean and tidy inside and appeared

weatherproof. Inside were some BAS stores, and some medicine from

an Argentinian medicine chest. There was also a large coal store

and a coal stove.

The shed contained various bits of junk, and three old

Argentinian fuel drums which still contained diesel fuel. Behind

the shed were a further three drums. All drums were.

deteriorating and two of those outside were beginning to leak.

Greenpeace personnel decanted the fuel from the two that were in

worst condition, and rolled all the barrels into the shed.

Near the hut was a burn drum, which showed signs of having

recently been used.

Greenpeace personnel discussed the problem of the fuel drums with

the OIC at Faraday, who said that the UK could not take

responsibility for removing abandoned fuel that belonged to the

Argentine government.

4.3 Conclusions and Recommendations

The hut at Peterman Island should be either properly maintained,

or removed completely. Argentina has primary responsibility for

the site, but the UK, which now uses the site most consistently,

should also take some initiative. If it is to be kept and

maintained, it should not be used during the breeding season.

Most urgently, remaining fuel and any other toxic substances

should be removed. This would not be a particularly arduous job,

and could be undertaken in a couple of hours by any ship in the

area.

Personnel visiting the hut should remove all their wastes with

them. The burning of rubbish seems completely unnecessary, and in

any case contrary to Annex III of the Protocol.

5 ARGENTINA: YANKEE HARBOUR

5.1 Location and Site Description

In Yankee Harbour, Greenwich Island, there is a small, one-

roomed hut, sitting in the middle of a large gentoo penguin

colony. There were also a few fur seals and elephant seals in the

vicinity of hut.

The hut is solid, but deteriorating. Its door was open, and

penguins had nested inside, covering the floor with guano. At

present, the hut is unusable and would require much work to make

it habitable.

Inside the hut were some Argentine navy plates, and the

navigation aid on the spit nearby was also Argentinian.

5.2 Comments and Recommendations

This structure should be completely removed and the area should

be cleaned up, by Argentina during the next summer season. This

operation should be undertaken after the wildlife in the

vicinity has finished breeding and has departed.

If there is a genuine need for a refuge in the area, one should

be built outside the penguin colony.

6 BRAZIL: BARAO DE TEFFE

6.1 Background Information

The Bardo de Teffe is the Brazilian resupply ship, run by the

Brazilian navy (Marinha Nacional do Brazil). It is a large ship,

carrying helicopters and a large helipad on the stern.

6.1.1 Date and Description of Contact

Greenpeace saw the Bardo de Teffe three times during January

1993; twice in Maxwell Bay, King George Island, on 7 and 9

January, and once in Admiralty Bay when it was resupplying the

Brazilian station, Ferraz, on 15 January.

A short but cordial radio conversation took place on 7 January.

However, attempts by Greenpeace to make contact during the

second encounter in Maxwell Bay (described further below) were

unsuccessful.

6.2 Compliance with the Protocol

On 9 January, when the Bardo de Teffe was stationed in Maxwell

Bay, Greenpeace watched and documented its helicopter operating

at low levels over Ardley Island, a designated Site of Special

Scientific. Interest (No. 33). Greenpeace saw the helicopter make

at least three passes over the island, including landing on the

highest point at least twice. It appeared to be deploying people

at the navigational mark at the peak of the island.

The Ardley Island SSSI management plan states (paragraph 2(vi)):

"Helicopters should not land on or overfly the island below 300 m

altitude."

Recommendation XVI-2, which annexes the management plan for

Ardley Island, says that the management plan should be

"voluntarily take[n] account of." The Madrid Protocol, Annex V

states that already-designated SSSIs be redesignated Antarctic

Specially Protected Areas (ASPAs), and that entry into the ASPAs

shall only be by permit, for purposes "in accordance with the

requirements of the Management Plan relating to that area."

6.2.1 Comments and Recommendations

Overflights of, and landing on, Ardley Island are a clear breach

of the Ardley Island SSSI management plan, and of the agreement,

made by governments in 1991 at the XVIth Antarctic Treaty

Consultative Meeting in Bonn, to apply the provisions of the

Madrid Protocol and its annexes even though they are not yet in

force.

The officers and crew of the Bardo de Teffe need urgent training

in the requirements of the Protocol and other Antarctic Treaty

requirements. Procedures should be implemented by Brazil to

ensure that such a violation of Antarctic Treaty System

agreements is not repeated.

7 BRAZIL: COMANDANTE FERRAZ

7.1 Overview

Brazil opened Comandante Ferraz Station in 1984. Logistics and

station maintenance are provided by the Brazilian navy (Marinha

Nacional do Brasil).

Brazil's National Committee for Antarctic Research, subsidised by

the National Research Council of Brazil, is responsible for the

liaison between the Brazilian Antarctic Program and the

Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR).

7.1.1 Location

Comandante Ferraz (62°05'S, 58°23'W) is situated in Admiralty

Bay, King George Island, South Shetland Islands. It sits on a

gently sloping gravel beach, less than 100 metres from the sea.

There are a couple of lakes behind and above the station.

7.1.2 Status

The OIC at the time of Greenpeace's visit was Capitao de Fragata

Jose Francisco Vasconcellos Gomes (Brazilian Navy). His term of

duty was from December, 1992 to March, 1993.

The station is staffed by two different crews per year, one for

the summer, and one for the winter, meaning that normally nobody

spends more than ten months at the station. Usually, there are 13

in the winter crew (8 navy and 5 scientists), while the

summer crew consists of 25 people (8 navy and 17 scientists).

However, at the time of Greenpeace's visit, there was an extra

crew of 25 construction workers (civilians working for the navy)

on station. Therefore, the total number of people sleeping at the

station on the inspection day was 48.

The navy personnel comprised three officers (the OIC, the second

in command, and the doctor) and five sergeants (mechanic, radio

operator, cook, etc.). Of the scientists, only men are permitted

to overwinter.

In running the station, the navy works in cooperation with other

government ministries such as the Comisao Interministerial de

Recursos do Mar (Interministerial Commission of Marine

Resources). Science is coordinated by the Conselho Nacional de

Desenvolvimiento Cientifico e Technologico (National Council of

Scientific and Technological Development).

7.1.3 Date and Description of Contact

Greenpeace visited Ferraz on 15 January 1993. The resupply ship

Barao de Teffe had arrived, and they were doing their mid-summer

resupply. Greenpeace therefore offered to come back the next day,

but the OIC was willing to host a visit that day. Despite also

supervising a hectic resupply, the second in command and doctor,

Sebastiao Vieira, conducted a tour of the station, after which

Greenpeace personnel were invited to lunch. Later in the day,

some of the station personnel briefly visited the Pelagic.

7.1.4 Previous Visits

Greenpeace previously visited Ferraz in November 1989, and

before that in April 1988.

7.2 Physical Structure

The station complex consists of 59 galvanised steel modules,

lined with wood and set in concrete foundations. Most modules are

linked by a common roof. Under the roof the ground is paved with

small, uncemented concrete blocks. Besides the central complex,

there are around eight other small buildings, including

laboratories, and the meteorological building. The structures

were all in good condition.

A road leads from the station to Point Plaza, some 900 metres

away, where there are several more laboratories. There is also

some tracking within the station area (from the station to some

of the labs up the hill).

Water is taken from the two freshwater ponds close to the

station.

7.2.1 New or Upgraded Facilities

The station has now reached its functional size and personnel did

not expect any expansion in the near future. At the time of

Greenpeace's visit, a new engine room was being installed within

the main complex. The main reason given for this was that the old

engine room had been located in the middle of the station and was

too noisy.

Another new project was the relocation of the helipad. Although

they were already using the new location, landing on the

unmodified ground surface, personnel said that an EIA would be

done when the time came to construct the new helipad.

7.3 Operations

There were 21 scientific programs at the station, in life,

atmospheric and earth sciences. At least half of the scientists

were from the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais.

One of the projects was addressing the environmental impact of

the station. Specifically, this project was assessing

hydrocarbon contamination, mostly in water bodies (sea and

lakes) but also in the terrestrial environment in the vicinity of

the fuel tanks. This project had been under way for several

years.

Botanical studies were being done in collaboration with

Canadian, Belgian and Japanese scientists.

In addition, other projects were addressing global change:

* mass balance of glaciers and its relation with global change;

* ozone measurements and hole displacement (in collaboration with

Magallanes University in Punta Arenas);

* ice coring to reconstruct evolution of environmental pollution

in the South Shetlands.

In summer, inflatable boats are the primary form of transport.

While there were seven on station, only three were in use at the

time of Greenpeace's visit, owing to a shortage of drivers. In

winter, they use three snow tractors, four snowmobiles with skis

available for recreation. There are also two bulldozers on

station.

7.3.1 Waste Disposal Systems

7.3.1.1 Separation

Garbage is divided into five categories: plastics, metal, glass,

organics and paper/wood/cardboard. The latter two categories are

incinerated, and the others are removed from the Antarctic, cans

being compacted first. Separation is done at source, into well-

marked bins in the kitchens and toilets. Statistics on the

amount of waste produced in each category are reported to SCAR.

The radio operator was in charge of waste disposal.

Apparently this system has always operated at this station.

There was no evidence of food being available to wildlife, and

there were only a couple of pairs of skuas hanging around the

station.

The laboratory sinks, into which chemical wastes are poured,

drain into plastic containers outside the laboratory.

7.3.1.2 Dumps

There was no dump visible at Ferraz. At the beginning and end of

each term of duty (summer and winter), station personnel carry

out what they call "Operacao pente fino" (fine comb operation) in

which they walk along the beach from Point Plaza about 900 metres

away, through the station, picking up litter. During the 1992/93

summer, the OIC reportedly had such litter patrols done every two

weeks.

The effectiveness of this regime was obvious in that, despite

being in the middle of a resupply and construction of an

extension of the station, there was almost no litter around the

station. Nor was there much beyond the station vicinity, apart

from around the abandoned British buildings on either side of the

station.

7.3.1.3 Incineration

Organics, paper, and wood were being incinerated in a hospital-

style high temperature incinerator located inside the roofed

complex. Emissions were filtered using "oxicatalyzers", which

eliminate carbon monoxide from the exhaust fumes by converting it

to carbon dioxide and water.

Ash is returned to Brazil.

7.3.1.4 Waste Removal

In addition to the other categories of waste, mentioned above,

that are removed, waste oil and fuel is stored in drums and

returned to Brazil.

7.3.2 Sewage System

Human waste and grey water were being treated in a three-

chambered septic tank, with filters between each chamber.

Filters were changed every two months. In the winter of 1992, a

new filtering system was installed that reportedly enables the

treatment of sewage produced by 150 people. After it has run

through the three filters, liquid seeps into the soil, and flows

in a small stream on the surface towards the sea, accumulating in

a 10-metre long pool at the top of the beach. A film of

grease could be seen on top of this pool, and algae had

accumulated on the rock surface over which the liquid flowed.

The specifications of the new filtering system require that it is

cleaned out after one year. However the OIC said that they would

clean it more frequently, experimenting to find the best

intervals.

7.3.3 Energy Systems

The station stored 330,000 litres of diesel, which is used in all

generators at the rate of approximately 20,000 litres a month.

Consumption will theoretically diminish with the new engines,

which had not yet been tried.

The inflatable boats used about 400 litres of gasoline a month

(in summer).

Diesel is stored in 17 cylindrical steel tanks of 20,000 litres

each. These are mounted horizontally on steel frames, sitting on

beach pebbles about 50 metres from, and ten metres above, the

shoreline. The tanks are connected to the generator room system

by steel pipes. There were no additional containment systems and

there were fuel stains in the soil around the tanks and most

other connections in the system.

Fuel is transferred in barges from the resupply ship to shore.

The barges are beached, and the fuel is transferred by flexible

hose to the tanks. Since Greenpeace's last visit, a new fuel

pipeline had been installed.

Previously, the station had three main generators plus two

emergency generators. These have been exchanged for five 150

kW/amp generators, housed in a new generator building, with two

extra ones for emergency use.

Along with the new generators, a filter has been installed on the

exhaust system. After going through the filter, exhaust passes

through a water tank to make use of the waste heat.

According to manufacturer's specifications, the filter has a low

initial and operational cost, as it does not require

electricity. It reportedly eliminates different substances in the

following percentages: 95% of carbon monoxide, 90% of soot, 85%

of formaldehyde, 10% of NOx, and 50% of noise. It does not

increase the production of NO2.

Fuel spills have occurred in the past. Two years ago, a spill

occurred in winter time. It was hidden by snow, and therefore

went undetected for some time. This spill was not cleaned up, but

its effects have been monitored. Apparently, little

biodegradation has taken place, and some compounds that

evaporated from the surface still persist deeper down.

At the time of Greenpeace's visit, station personnel reported

that there was an oil spill contingency plan for the station

being developed by PetroBras (the Brazilian oil company) in

collaboration with Sao Paulo University scientists studying oil

contamination.

There were no plans to introduce alternative energy systems to

the station. The station seemed to be somewhat inefficient in its

use of energy, in that it was kept at a relatively high

temperature inside the buildings, through the use of electric

heaters.

7.3.4 Resupply Operations

The navy resupply ship Barao de Teffe normally visits the

station twice a year to exchange crews, although in the 1992/93

summer it also visited in January for a mid-summer change of

scientists. There are also seven flights a year, which use the

Chilean airstrip at Marsh. Another resupply ship, the Professor

W. Besnard, is also sometimes used.

7.4 Tourism

Ferraz received four tourist visits in the six weeks previous to

Greenpeace's visit. Apparently tourist companies tend to take

their ships to either Arctowski or Ferraz, but not both.

Tourists are briefed by the tour operators before coming ashore

and in general personnel do not consider them to be a problem.

Tourists are asked to follow a set route that takes them around

the station, to the abandoned British huts, and to visit the

whale skeleton. The moss bed on which the skeleton sits is

marked as off-limits, and is delimited on the ground by a

perimeter of small rocks.

7.5 Evaluation of Environmental Impact

When asked what he thought the greatest impacts of the station

were, the OIC said that the worst impacts had come during the

station's construction, and added that he did not expect them to

increase with time, due to the way the station is run.

The engineer in charge of construction said that a preliminary

assessment had been done prior to the construction of the

buildings.

The OIC told Greenpeace that station personnel are careful not to

feed wildlife, particularly as they had heard of other

stations having trouble with faecal contamination of water

supplies by the birds that are encouraged to hang around.

Prior to travelling to Antarctica, Brazilian personnel receive a

lecture about the systems in operation at the station, safety

issues and behaviour with respect to the environment. In

addition, preparations for the winter crew include survival

training and medical and psychological tests. The lecture is

reinforced with another given on arrival at the station,

although the one given to the new arrivals on the day that

Greenpeace visited referred only to domestic matters. However,

this may have been because most of the newcomers had been to the

station before.

On arrival at the station, three papers were given to Greenpeace

personnel. One was a visitors' introduction (in English) to the

history of the station, with a biography of C. Ferraz; another

was a map of the station (in English) showing a route for

touring the station and vicinity and the third was page of

instructions about protecting the environment, litter, safety and

science (in English and Portuguese). The last was very

similar to those given to us at Bellingshausen and Arctowski.

Near the station there are substantial moss beds, in particular

around the whale skeleton assembled several years ago by Jacques

Cousteau. These areas are forbidden to personnel and visitors.

7.5.1 Compliance with the Protocol

There were copies of the Protocol on station, and personnel

generally seemed well informed about its implications. However,

some scientists complained that in their normal jobs back in

Brazil it was difficult to stay updated about what was happening

in the Antarctic Treaty system.

The station managers believed that only small adjustments in the

way the station is run will be needed to comply with the

Protocol. Mostly these will involve the way environmental impact

assessment is developed.

7.5.2 Comments and Recommendations

Overall, the impression was of a well-run station, with a high

level of environmental awareness, and a high degree of

importance placed on the science program.

All the personnel that Greenpeace talked to seemed to be aware of

their environment and of the new developments of the

Antarctic Treaty including the Protocol. The OIC and other

military personnel emphasised their role of support for science.

The use of uncemented bricks as a paving material would seem to

be sensible, as they will be able to be removed when the time

comes to take the base out.

Incineration of waste should be phased out, and all waste should

be removed from the Antarctic instead.

Fuel handling needs to be done with more care, and containment

should be provided around all fuel facilities. The amount of fuel

used by this station could be reduced by lowering the

temperature of the station, and by developing alternative

sources of energy.

7.6 Abandoned British Facilities

At either end of the beach on which Ferraz is located are

abandoned British facilities. One is part of an old whaling

station, and the other was Falkland Islands Dependency Survey

(FIDS) Base G. To the north, on a low headland, are two

buildings. One is quite small and contains a toilet but little

else. The other is large, and has a central corridor running its

length, with smallish rooms either side. It is still

structurally complete, but is decaying. The rooms contained much

rusting and decaying junk, the building smelt, and one room was

full of mouldering cans. Fortunately, there is little junk lying

around outside these buildings.

To the south, again on a small headland and next to three

Brazilian buildings (including the meteorological building), are

another two buildings. The smaller one is a shed, which now

contains mainly Brazilian construction materials and other junk

(including PVC piping lying on the ground). The large building is

a complex of rooms. The roof is falling in (and in fact has

disappeared) in several places, and the contents (mattresses,

food, remains of the workshop, etc.) were therefore in poor

condition and were scattered around the rooms. Outside there were

several places where stacks of coal had split and were spreading

over the ground. Inside one room were two vehicle batteries

decaying on the bench.

It looked as though the place had been looted because all the

drawers were open, and wiring had been pulled off the walls in

many places.

7.6.1 Recommendations

These buildings should to be tidied and either removed, or

declared and maintained as historic sites, by the UK government

as a matter of urgency. Of most urgency, hazardous materials such

as chemicals and batteries need to be removed, as well as any

tangled wiring or other junk that might prove a hazard to

wildlife.

8 BULGARIA: REFUGE

8.1 Overview

The Bulgarian hut on Livingston Island was installed by Sofia

University in April 1987. As far as can be established, it has

not been used since. The OIC at the nearby Spanish station, Juan

Carlos I, said that she had visited and documented the site

several times over the past few years, and that it is steadily

deteriorating.

Some of the construction materials and drums have disappeared

over time, and sometimes debris from the site are found on the

other side of the bay.

8.1.1 Location

This refuge is situated in the head of South Bay. It is set a

couple of hundred metres back from the shore, approximately 10

metres above sea level.

8.1.2 Date and Description of Contact

Greenpeace visited the site on 21 January 1993, for

approximately one hour.

8.2 Description of Physical Structure

The refuge consists of two buildings, both about the size of a

small shipping container. One, constructed of wood, sits